The Red List and protection issues: the Noah’s Ark problem

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List is an indicator that makes it possible to monitor the state of biodiversity in the world. Thanks to this inventory, we now know that one in four mammal species, one in seven birds, more than one in three amphibians and one third of conifer species are threatened with extinction worldwide. These alarming figures unfortunately affect more and more species, and one wonders how these lists influence biodiversity protection programmes. Joël White, a professor of ecology at the University of Toulouse and Vice-President of A Rocha France, spoke to us about this issue.

© Bill Roque’s Images

Marie Pfund (MP): Hi Joël, is there now a prioritisation of animal species protection according to the IUCN categories? If so, to what extent?

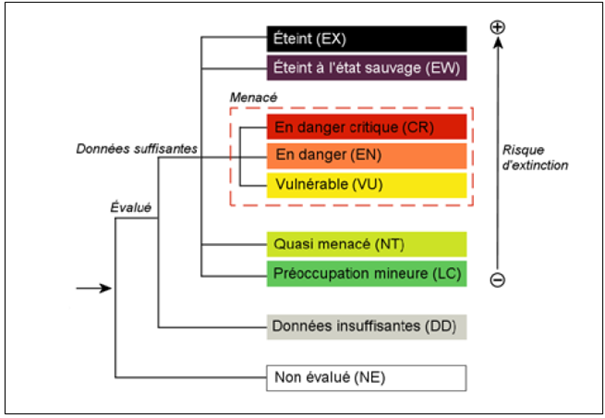

Joël White (JW): The IUCN Red List is a reference tool for the global conservation status of many animal and plant species. It lists the level of threat to each species in 9 categories (see figure below). This level of threat is obviously one of the criteria used when prioritising conservation actions: a habitat containing many red-listed species can be identified as being in need of priority protection. However, scientists believe that other criteria should be taken into account, such as phylogenetic criteria (is the species in question the only one in its group or are there other species related to it?) or functional criteria (does the species in question have a specific function or is it particularly important in the ecosystem?). What is certain is that it is much more useful to seek to preserve entire ecosystems with a diversity of species than to focus on one species, no matter how vulnerable it is.

MP: How were these categories constructed historically?

JW: The first red list published in 1964 contained only 204 species of mammals and 312 species of birds and classified them in 4 categories. The current 9 categories have been in use since 2001 and the IUCN now assesses over 147,000 species, which is already a great achievement. Although the list initially focused on the best-known species such as birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, the IUCN is now trying to assess other groups such as invertebrates, plants and fungi. But the task is far from complete: while 85% of the four groups mentioned above have been assessed, this is only the case for 67% of fish, 14% of plants, 2% of invertebrates and 0.4% of fungi. In total, only 7% of the 2 million species described by science to date are sufficiently studied to be assessed by IUCN. This tells us that the decline in living things that we are seeing is in fact the tip of a huge iceberg that is melting away.

IUCN Red List categories

MP: What is the current trend within the different categories?

J.W: Today, 28% of the species listed by the IUCN are threatened and this proportion is increasing. Although there are some positive trends, such as the tiger, whose populations have recently been revised upwards, the vast majority of changes in status indicate a worsening conservation status for threatened species.

MP: If the number of ‘critically endangered’ species continues to rise in the future, is it realistic to think that we will have to select which species to save (and therefore which to let go extinct)?

JW: Given the limited resources and finances available to conservationists, they will increasingly find themselves (and are already!) in the unenviable position of having to make choices. Should conservation efforts be concentrated on one region/area or another? This is what Anglo-Saxon conservation biologists call ‘the agony of choice’ or ‘the Noah’s Ark problem’. Here again, we come up against the problem of prioritisation criteria. Should the areas with the greatest species diversity be protected? If so, what type of diversity (taxonomic, phylogenetic, functional)? Or should we concentrate on those with the most threatened species? On the contrary, we could focus on the species with the least risk of becoming extinct in the short or medium term so as not to ‘waste’ our efforts. As you can see, this question is extremely difficult to resolve, even from a purely rational and scientific point of view.

MP: Doesn’t this also pose an ethical problem?

JW.: I’m not a specialist in ethics, but it seems complicated to me to say that one species has more value than another and to set up a scale of value for the millions of species that inhabit this earth. We could take an anthropocentric view and consider the species that are most ‘useful’ to humans, but we can see the damage that this view has caused over the past few centuries. For example, of the 7,000 species of plants used by humanity in the pre-industrial era, only 12 now make up almost all of the world’s food (Esquinas-Alcazar 2005 Nature Review). Similarly, the 4 livestock species used for global food constitute 60% of the total mammalian biomass on the planet compared to only 4% for the 6000 species of wild mammals – the remaining 36% is the total biomass of humans (Bar-On et al 2018 PNAS). In addition to the impact on biodiversity, the overdevelopment of a handful of species that seem to us to be the most useful leads to numerous problems associated with monoculture: reduced genetic diversity (vulnerable to pathogens, climate change), uniformity and therefore soil erosion, increased dependence on pesticides and fertilisers, etc…

MP: Is there a biblical view on this issue?

JW: I believe that the Bible shows the importance and value that God places on each of the species that He created. In Matthew 10:29-31, Jesus says that not a single sparrow (an insignificant species to the people of the time) falls to the ground without God’s care. Genesis, some of the Psalms and sections of Job also show how God rejoices in all the diversity of species He has created. Dave Bookless, pastor, author and theological director of A Rocha International (and speaker at the Eco-Theology seminar at Les Courmettes) writes in his book Planetwise that each species reveals something unique about God. Every time one of them disappears, it is as if we are erasing a ‘footprint’ of God in this world.

MP: Finally, what can be done to avoid having to make such a selection?

JW: Conservation actions are absolutely necessary and useful, but their effects will be derisory if they are not accompanied by a radical change in our individual behaviours and the way our Western societies function. It is our over-consumption, our agri-food system with all the harmful effects of intensive agriculture and our Western lifestyle that have the greatest impact on global and local biodiversity.

MP: What is A Rocha doing around the protection of biodiversity and in particular the red list species?

JW: 1.2 million hectares of natural areas on five continents have benefited from A Rocha’s protection and restoration actions, as well as 431 threatened species. Simon Stuart, the current Director of A Rocha International, is a former member of the IUCN Committee and has contributed significantly to the development of the current Red List. In France, 37,500 ha and some 40 threatened species have been positively impacted by our interventions. As actions to protect biodiversity are only effective if they are accompanied by a change in our collective and individual behaviour, A Rocha also works to raise awareness of the reality of the ecological crisis and of our responsibility, notably through its Ambassadors network.

What do you think about this article? Send us your feedback!